Skechers GOrun Ultra Road 2 Review

I have approached the maximalist shoe trend with caution. While I will admit that I have some minimalist tendencies (recovering minimalist shoe person) there are some potential biomechanical issues with many max cushion shoes that I have seen come to light. A lack of flexibility, decreased foot proprioception, decreased shock attenuation at the ankle (which could be a good or bad thing depending on the condition). That all changed when I got my hands on a pair of Skechers GOrun Ultra Road 2. Although this is a maximalist shoe based on stack height, the Ultra Road 2 is different.

Sunday, August 27, 2017

Sunday, August 20, 2017

Running Injury Prevention: The Sciatic Nerve and Lower Extremity Flexibility

Running Injury Prevention: The Sciatic Nerve and Lower Extremity Flexibility

Piriformis, hamstring and calf muscle tension very common in runners. Some may argue this comes from excessive use and adaptation of the muscular system. The increased tension means more efficient springs and better energy conservation. This is fine if the muscles remain elastic but not tight to the point that normal motion is restricted. . Many runners are well aware of extreme tightness that can occur in these areas. Hamstring and calf injuries along with piriformis syndrome are common in the running population. Often the extreme tension is from a lack of flexibility training and weakness of muscles elsewhere that these muscle groups are compensating for (glutes or ankle stabilizers). So many people go about a normal flexibility routine after every run or so and try to work on balancing themselves out strength wise. Sometimes though.... that muscle tension doesn't go away. In fact it keeps getting worse. As a clinician, that's when I start to suspect involvement of the sciatic nerve.

As always, my views are my own. My blog should not and does not serve as a replacement for seeking professional medical care. I have not evaluated you in person, am not aware of your injury history and personal biomechanics, thus am not responsible for any injury that you may incur from the performance of the above. I have not prescribed any of the above exercises to you and thus again am not responsible for any injury that may occur from the performance of the above. This blog is meant for educational purposes only. If you are currently injured or concerned about an injury, please see your local physical therapist. However, if you are in the LA area, I am currently taking clients for running evaluations.

Dr. Matthew Klein, PT, DPT

Orthopedic Resident - Casa Colina

References

Shacklock, M. (2005). Clinical Neurodynamics. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Noakes, T. (2003). Lore of Running - Fourth Edition. Champaign, Il: Human Kinetics

Perry, J. (1992). Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function. Thorafare, NJ: SLACK Incorporated.

Like and Follow Kleinruns DPT

Facebook: Kleinruns DPT Twitter: @kleinruns

Instagram: @kleinrunsdpt Direct Contact: kleinruns@gmail.com

Piriformis, hamstring and calf muscle tension very common in runners. Some may argue this comes from excessive use and adaptation of the muscular system. The increased tension means more efficient springs and better energy conservation. This is fine if the muscles remain elastic but not tight to the point that normal motion is restricted. . Many runners are well aware of extreme tightness that can occur in these areas. Hamstring and calf injuries along with piriformis syndrome are common in the running population. Often the extreme tension is from a lack of flexibility training and weakness of muscles elsewhere that these muscle groups are compensating for (glutes or ankle stabilizers). So many people go about a normal flexibility routine after every run or so and try to work on balancing themselves out strength wise. Sometimes though.... that muscle tension doesn't go away. In fact it keeps getting worse. As a clinician, that's when I start to suspect involvement of the sciatic nerve.

Image from Biology Stack Exchange

ANATOMY

The sciatic nerve is the major nerve to the lower leg. It is made up of the L4 to S3 nerve roots from the spinal cord. The nerve roots come together and pass in or underneath (depending on your anatomy) the piriformis muscle deep in the hip. From there it exits the pelvis, passes through the hamstring muscle group close to the adductor magnus. As it hits the knee, the sciatic nerve splits into the common fibular and tibial nerve portions. The fibular nerve curves around and passes in front of the lower leg and innervates all the dorsiflexors and toe extensor muscles. The tibial nerve passes behind the solueus and controls all of the calf muscles. The tibial portion also continues into the plantar aspect of the foot and controls many of the intrinsic toe muscles.

The sciatic nerve is the major nerve to the lower leg. It is made up of the L4 to S3 nerve roots from the spinal cord. The nerve roots come together and pass in or underneath (depending on your anatomy) the piriformis muscle deep in the hip. From there it exits the pelvis, passes through the hamstring muscle group close to the adductor magnus. As it hits the knee, the sciatic nerve splits into the common fibular and tibial nerve portions. The fibular nerve curves around and passes in front of the lower leg and innervates all the dorsiflexors and toe extensor muscles. The tibial nerve passes behind the solueus and controls all of the calf muscles. The tibial portion also continues into the plantar aspect of the foot and controls many of the intrinsic toe muscles.

PATHOLOGY

Notice how close that nerve gets to or goes through several muscles that are commonly tight? The piriformis, hamstrings and calf muscles are all muscles that get tend to get tight in runners. When those muscles are either over utilized or become to tight, they can compress the sciatic nerve (or the various branches). Nerves in the body do not like being compressed or statically stretched. They have specific canals they need to slide and glide through for optimal function. So when they get stuck or compressed, the muscles they innervate may start to get tight. Common signs of nerve compression or irritation may include numbness, tingling, burning, chronic tightness and/or chronic pain.

Image from Runner's World

BIOMECHANICS

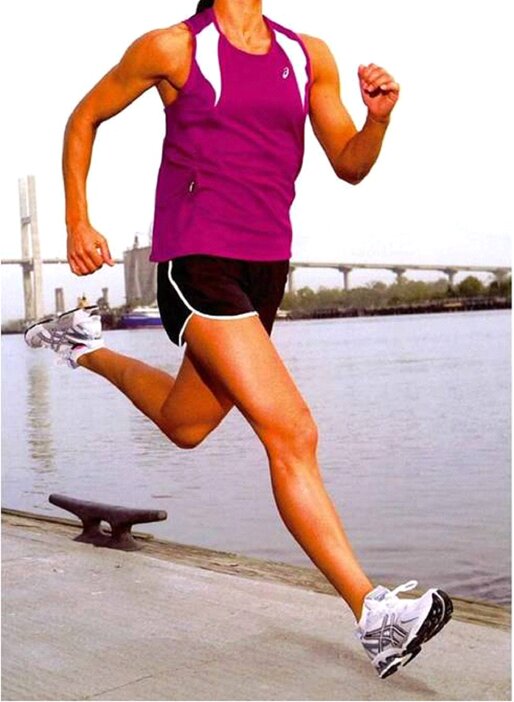

The sciatic nerve has the most tension placed upon it with hip flexion, knee extension and ankle dorsiflexion (further tension can be create from spinal flexion and other things from higher up the chain but that is for another post). Combining all three of those at the same time and holding it is a great way to stretch and irritate this nerve. So the classic hamstring stretch that people do where they also pull their ankles into dorsiflexion? That's not your hamstring getting stretched. That would be you attempting to statically stretch a tissue that is not supposed to do that. As I briefly mentioned earlier, nerves do not stretch but instead must glide and slide through specific canals in the body as we move. Given that they do not stretch, those canals need to be kept open for optimal movement. Normal compression or stretch will occur with certain activities, kicking a soccer ball for example (that usually involves hip flexion, knee extension and ankle dorsiflexion) but they must only occur for a brief moment and not repeatedly for long periods of time. Those most likely to be irritated by overly stretching the sciatic nerve in the running population are those that tend to overstride. As you can see from the photo below, most people that tend to overstride (and you know you've seen this) usually put themselves in a position that would create tension on the sciatic nerve (hip flexion, knee extension, ankle dorsiflexion). Now imagine that you keep trying to do that and the nerve is caught somewhere in the lower extremity. You are continually pulling on something that does not like being excessively stretched. Does it make sense why you may have continual tension is certain areas? That may be from you continuing to pull on that nerve.

Image from SBR Sport. Hip flexion, Knee Extension and Ankle Dorsiflexion. Add the additional compressive load from landing hard in front of you and this may put you at risk for irritating and excessively stretching the sciatic nerve.

EXERCISES

To help those nerves move a little better, we can use techniques called nerve flossing. This can isolate the common areas of tension and help the sciatic (or distal branch of the sciatic) nerve glide better through those canals. What is very cool about these techniques is that you may see an improvement in flexibility and decrease in pain after doing these (you may also have increased soreness but SHOULD NOT have pain). Why? Because when you reduce tension on a nerve, the muscles innervated by that portion will generally relax. When a nerve is compressed, it tends to send odd signals to the tissues it innervates. This tends to bring on a protective reflex in the muscles, leading to increased tension. Reduce the threat to reduce the tension. These techniques should be done for no more than 5 minutes at a time and should always be done SLOWLY. I usually start people out with 2-3 sets of 15-20 oscillations or 2-3 sets of 1-2 minutes. DO NOT HOLD THESE STATICALLY! Use a strap (like the Stretch-Out Strap or a dog leash) to help hold the foot. Once you finish with these techniques, then go back to your normal calf, hamstring and piriformis stretches and you may find that some of that flexibility stays.

To help those nerves move a little better, we can use techniques called nerve flossing. This can isolate the common areas of tension and help the sciatic (or distal branch of the sciatic) nerve glide better through those canals. What is very cool about these techniques is that you may see an improvement in flexibility and decrease in pain after doing these (you may also have increased soreness but SHOULD NOT have pain). Why? Because when you reduce tension on a nerve, the muscles innervated by that portion will generally relax. When a nerve is compressed, it tends to send odd signals to the tissues it innervates. This tends to bring on a protective reflex in the muscles, leading to increased tension. Reduce the threat to reduce the tension. These techniques should be done for no more than 5 minutes at a time and should always be done SLOWLY. I usually start people out with 2-3 sets of 15-20 oscillations or 2-3 sets of 1-2 minutes. DO NOT HOLD THESE STATICALLY! Use a strap (like the Stretch-Out Strap or a dog leash) to help hold the foot. Once you finish with these techniques, then go back to your normal calf, hamstring and piriformis stretches and you may find that some of that flexibility stays.

Hip Floss. Oscillate between hip flexion and extension with the knee straight and the ankle held in dorsiflexion.

Hip Sciatic Nerve Floss

For those with chronic hip or upper hamstring tightness, mobilizing the sciatic nerve at this point may be helpful. Lie on your back, keep your knee straight, keep your foot dorsiflexed as much as you can. Bring your leg up until you feel tension in the hamstring or calf. Use a rope of some kind to oscillate between hip flexion and extension. DO NOT push into pain or extreme tension. Go up right before that happens but no farther. You do not want to aggravate your nerves. You want them to move better.

Knee Floss. Oscillate between knee extension and flexion with the hip at 90 degrees and the ankle held in dorsiflexion.

Knee Sciatic Nerve Floss

For those with tension behind the middle knee, chronic hamstring or calf tightness. Lie on your back, bring your hip to 90 degrees of flexion, grab a rope and pull your dorsiflexed foot up to where you feel tension in the hamstring, calf or hip. Keep your foot dorsiflexed and oscillate between knee flexion and extension. DO NOT push into pain or extreme tension. Go up right before that happens but no farther. You do not want to aggravate your nerves. You want them to move better.

Ankle Floss: Hold the hip still and the knee straight while you oscillate your ankle between dorsiflexion and plantarflexion.

Ankle Sciatic Nerve Floss

This technique is very similar to the hip nerve floss. For those with chronic calf tightness. Lie on your back and position yourself exactly as you did for the hip technique. This time however the hip should not move and you should oscillate your ankle between dorsilflexion and plantarflexion. DO NOT push into pain or extreme tension. Go up right before that happens but no farther. You do not want to aggravate your nerves. You want them to move better. I'm repeating this three times because this is a common mistake my patients make.

Conclusion.

So for those with chronically tight hamstrings or calf muscles, mobilizing the sciatic nerve at any of the above three spots may worth be a try. Nerve mobility is very important for normal flexibility and function. This is often overlooked and is important to check prior to aggressive stretching. It is important to not statically stretch nerves. That can irritate or inflame them. All nerve mobilizations should be performed as 1-2 second occilitations that should never be taken past the point of pain. I will also have a future post on the piriformis and the external rotators of the hip to address further address areas of sciatic nerve compression at the hip. Muscle and body soreness is normal after these techniques. More pain is not. If you continue to have pain please see your local healthcare professional. While these techniques work well for nerve mobility, if they do not help there may be a different pathology present.

Thanks for reading and don't forget to tack on!

Dr. Matthew Klein, PT, DPT

Orthopedic Resident - Casa Colina

References

Shacklock, M. (2005). Clinical Neurodynamics. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Noakes, T. (2003). Lore of Running - Fourth Edition. Champaign, Il: Human Kinetics

Perry, J. (1992). Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function. Thorafare, NJ: SLACK Incorporated.

Like and Follow Kleinruns DPT

Facebook: Kleinruns DPT Twitter: @kleinruns

Instagram: @kleinrunsdpt Direct Contact: kleinruns@gmail.com

Please feel free to reach out, comment and ask questions!

Sunday, August 6, 2017

Running DPT Injury Prevention: The Iliotibial Band

Running DPT Injury Prevention: The Iliotibial Band

The iliotibial band can be a major source of problems for many runners. Even mentioning that structure can strike fear in the hearts of athletes in many sports, especially distance running. This structure is actually very unique and provides a great deal of stability to the knee and lower extremity. The structure itself is not usually what causes the problems. It is far more often that the structure is being abused by the individual it is on!

ANATOMY

The iliotibial Band (or tract) is a fibrous band of tissue on the lateral aspect of the femur. Both the tensor fascia latae and the gluteus maximus attach to it at the hip. The band then travels down to Gerdy's tubercle on the lateral knee.

BIOMECHANICS

The iliotibial band is a unique structure. It stabilizes knee in both when it is in extension and slight flexion. Thus, the band will be pulled taught through the early part of stance phase, especially at initial contact and may be pulled tight again as the runner's lower extremity goes behind them. This makes sense as the tensor fascia latae and glute max are known to work to stabilize the femur, which is half of the knee joint. The iliotibial band is an extension of those two muscles and thus may aid in some minor degree in flexion and extension of the lower extremity. The primary function is to stabilize the lateral knee, especially given that both the muscles that insert upon it are major abductors of the hip.

ILIOTIBIAL BAND SYNDROME

Iliotibial band syndrome and pain will usually occur first during the initial contact phase of gait in about 20-30 degrees of knee flexion (Orchard, Fricker, Abud, Mason, 1996). Research has demonstrated those with iliotibial band issues many times have weak hip abductors and external rotators (Aderem & Louw, 2015; Noehren et al., 2016). Additionally further research has also demonstrated increased hip adduction and internal rotation as further biomechanical markers of this issue (Ferber, Noehren, Jamill, Davis, 2010). As the ITB is an extension of the TFL and glute max, going into excessive hip adduction will put strain on this fibrous band due to the function of trying to stabilize the lateral knee. The internal rotation aspect in my mind may suggest either a dominance of the TFL over the glute max or hip external rotator weakness as the anatomy of the hips usually play into internal rotation during joint loading (but this needs to be controlled muscularly).

EXERCISES

Given that the ITB is strained in runners who have excessive adduction and internal rotation, there is a need to strengthen the hip abductors and external rotators. Foam rolling may help short term but will not fix the problem (I will have a post on foam rolling in the future. The short version is that it likely affects your nervous system more than the structures you are rolling).

TFL Stretch

Although the TFL is a hip abductor, the fact that it is an internal rotator makes the overuse of the structure a possible source for iliotibial band syndrome. Keeping this muscle from getting overused and shortened is important in preventing excessive loading of the iliotibial band. For this reason, the above stretch is important as is the exact way you execute it. Make sure you put the leg that is being stretched far enough behind you into extension and adduction (the TFL is a hip flexor) with some slight external rotation. Yes the adduction component you would think would cause problems, but this will be taken care of by the performance of the exercises below. Addressing the internal rotation component of the TFL is more important.

Squat with Band

It is important to train the neuromuscular system and the muscular system to maintain a neutral knee position during squatting. Running is essentially a series of single leg squats, so double leg squats are a great place to start. The use of a band helps to facilitate the neutral knee position by reinforcing the hip external rotators and abductors. You should maintain constant tension through the theraband as you go down AND up.

Side Bridge

A powerful hip abductor exercise I picked up from Stuart Mcgill, The side bridge brings aspects of the traditional clamshell, adds a side plank/ core and a weight bearing component. This is a very easy exercise to cheat through, so make sure to squeeze your butt checks throughout the range of motion both up and down. If this is too hard, start with a static side plank first from your knees, then progress up to this.

Conclusion

The iliotibial band is a very important structure that helps to stabilize your lower extremity and helps extend the reach of some of your hip abductors. Make sure you keep it healthy! Unless you have biomechanical factors that increase your risk for internally rotated or adducted positions of the hip, femur and knee (femoral anteversion, coxa vara, tibial torsion, etc), iliotibial band syndrome is fairly simple if caught early. The above exercises however can be quite challenging to execute properly. Anyone can give you an exercise, only an expert can explain to do it correctly. If you continue to have trouble, please contact your local running physical therapist.

As always, my views are my own. My blog should not and does not serve as a replacement for seeking professional medical care. I have not evaluated you in person, am not aware of your injury history and personal biomechanics, thus am not responsible for any injury that you may incur from the performance of the above. I have not prescribed any of the above exercises to you and thus again am not responsible for any injury that may occur from the performance of the above. This blog is meant for educational purposes only. If you are currently injured or concerned about an injury, please see your local physical therapist. However, if you are in the LA area, I am currently taking clients for running evaluations.

Dr. Matthew Klein, PT, DPT

Orthopedic Resident - Casa Colina

Like and Follow Kleinruns DPT

Facebook: Kleinruns DPT Twitter: @kleinruns

Instagram: @kleinrunsdpt Direct Contact: kleinruns@gmail.com

References

Aderem, J. & Louw, Q. (2015). Biomechanical risk factors associated with iliotibial band syndrome in runners: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 16: 356.

Middlekoop, M., Kolkman, J., Ochten, J., Bierma-Zenstra, S., Koes, B. (2007). Prevalence and incidence of lower extremity injuries in male marathon runners. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. doi: 10.1111/j1600-0838.2007.00683.x

Noakes, T. (2003). Lore of Running - Fourth Edition. Champaign, Il: Human Kinetics

Noehren, B., Davis, I., Hamill, J. (2007). Prospective study of the biomechanical factors associated with iliotibial band syndrome. Clinical Biomechanics, 22: 951-956.

Noehren, B., Schmitz, A., Hempel, R., Westlake, C., Black W. (2014). Assessment of Strength, Flexibility and Running Mechanics in Men With Iliotibial Band Syndrome. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 44(3): 217-222

Orchard, J., Fricker, P., Abud, A., Mason, B. Bioemchanics of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Runners. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 24(3): 375-379

Perry, J. (1992). Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function. Thorafare, NJ: SLACK Incorporated.

The iliotibial band can be a major source of problems for many runners. Even mentioning that structure can strike fear in the hearts of athletes in many sports, especially distance running. This structure is actually very unique and provides a great deal of stability to the knee and lower extremity. The structure itself is not usually what causes the problems. It is far more often that the structure is being abused by the individual it is on!

ANATOMY

Image from web.duke.edu

The iliotibial Band (or tract) is a fibrous band of tissue on the lateral aspect of the femur. Both the tensor fascia latae and the gluteus maximus attach to it at the hip. The band then travels down to Gerdy's tubercle on the lateral knee.

BIOMECHANICS

The iliotibial band is a unique structure. It stabilizes knee in both when it is in extension and slight flexion. Thus, the band will be pulled taught through the early part of stance phase, especially at initial contact and may be pulled tight again as the runner's lower extremity goes behind them. This makes sense as the tensor fascia latae and glute max are known to work to stabilize the femur, which is half of the knee joint. The iliotibial band is an extension of those two muscles and thus may aid in some minor degree in flexion and extension of the lower extremity. The primary function is to stabilize the lateral knee, especially given that both the muscles that insert upon it are major abductors of the hip.

ILIOTIBIAL BAND SYNDROME

Image from Move Forward PT

Iliotibial band syndrome and pain will usually occur first during the initial contact phase of gait in about 20-30 degrees of knee flexion (Orchard, Fricker, Abud, Mason, 1996). Research has demonstrated those with iliotibial band issues many times have weak hip abductors and external rotators (Aderem & Louw, 2015; Noehren et al., 2016). Additionally further research has also demonstrated increased hip adduction and internal rotation as further biomechanical markers of this issue (Ferber, Noehren, Jamill, Davis, 2010). As the ITB is an extension of the TFL and glute max, going into excessive hip adduction will put strain on this fibrous band due to the function of trying to stabilize the lateral knee. The internal rotation aspect in my mind may suggest either a dominance of the TFL over the glute max or hip external rotator weakness as the anatomy of the hips usually play into internal rotation during joint loading (but this needs to be controlled muscularly).

EXERCISES

Given that the ITB is strained in runners who have excessive adduction and internal rotation, there is a need to strengthen the hip abductors and external rotators. Foam rolling may help short term but will not fix the problem (I will have a post on foam rolling in the future. The short version is that it likely affects your nervous system more than the structures you are rolling).

TFL Stretch

Although the TFL is a hip abductor, the fact that it is an internal rotator makes the overuse of the structure a possible source for iliotibial band syndrome. Keeping this muscle from getting overused and shortened is important in preventing excessive loading of the iliotibial band. For this reason, the above stretch is important as is the exact way you execute it. Make sure you put the leg that is being stretched far enough behind you into extension and adduction (the TFL is a hip flexor) with some slight external rotation. Yes the adduction component you would think would cause problems, but this will be taken care of by the performance of the exercises below. Addressing the internal rotation component of the TFL is more important.

Squat with Band

It is important to train the neuromuscular system and the muscular system to maintain a neutral knee position during squatting. Running is essentially a series of single leg squats, so double leg squats are a great place to start. The use of a band helps to facilitate the neutral knee position by reinforcing the hip external rotators and abductors. You should maintain constant tension through the theraband as you go down AND up.

Side Bridge

A powerful hip abductor exercise I picked up from Stuart Mcgill, The side bridge brings aspects of the traditional clamshell, adds a side plank/ core and a weight bearing component. This is a very easy exercise to cheat through, so make sure to squeeze your butt checks throughout the range of motion both up and down. If this is too hard, start with a static side plank first from your knees, then progress up to this.

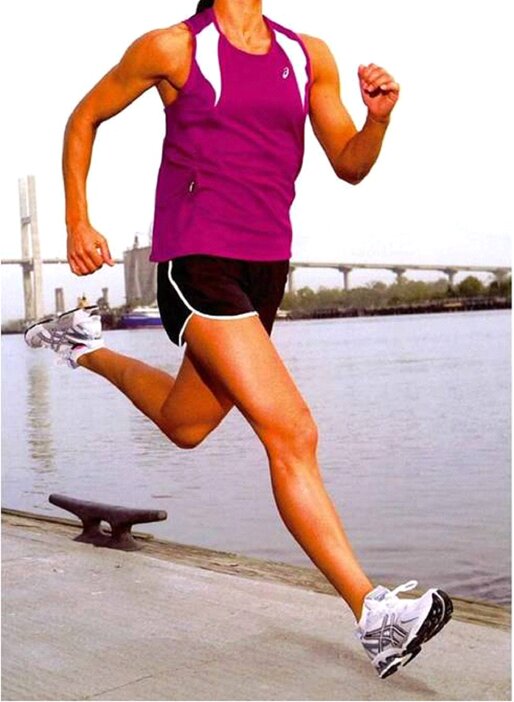

Example of good mechanics versus mechanics that may play you at risk for ITB Syndrome. Notice the hip adduction on the photo on the right side.

Conclusion

The iliotibial band is a very important structure that helps to stabilize your lower extremity and helps extend the reach of some of your hip abductors. Make sure you keep it healthy! Unless you have biomechanical factors that increase your risk for internally rotated or adducted positions of the hip, femur and knee (femoral anteversion, coxa vara, tibial torsion, etc), iliotibial band syndrome is fairly simple if caught early. The above exercises however can be quite challenging to execute properly. Anyone can give you an exercise, only an expert can explain to do it correctly. If you continue to have trouble, please contact your local running physical therapist.

Thanks for reading and don't forget to tack on!

Dr. Matthew Klein, PT, DPT

Orthopedic Resident - Casa Colina

Like and Follow Kleinruns DPT

Facebook: Kleinruns DPT Twitter: @kleinruns

Instagram: @kleinrunsdpt Direct Contact: kleinruns@gmail.com

Please feel free to reach out, comment and ask questions!

References

Aderem, J. & Louw, Q. (2015). Biomechanical risk factors associated with iliotibial band syndrome in runners: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 16: 356.

Middlekoop, M., Kolkman, J., Ochten, J., Bierma-Zenstra, S., Koes, B. (2007). Prevalence and incidence of lower extremity injuries in male marathon runners. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. doi: 10.1111/j1600-0838.2007.00683.x

Noakes, T. (2003). Lore of Running - Fourth Edition. Champaign, Il: Human Kinetics

Noehren, B., Davis, I., Hamill, J. (2007). Prospective study of the biomechanical factors associated with iliotibial band syndrome. Clinical Biomechanics, 22: 951-956.

Noehren, B., Schmitz, A., Hempel, R., Westlake, C., Black W. (2014). Assessment of Strength, Flexibility and Running Mechanics in Men With Iliotibial Band Syndrome. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 44(3): 217-222

Orchard, J., Fricker, P., Abud, A., Mason, B. Bioemchanics of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Runners. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 24(3): 375-379

Perry, J. (1992). Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function. Thorafare, NJ: SLACK Incorporated.

Tuesday, August 1, 2017

Footwear Science: Forefoot Arch Support

By Chief Editor Matt Klein

Some of the more common questions I get regarding footwear is whether an individual has enough arch support or how much stability a shoe has. While stability can come from a variety of places, the footwear industry generally describes stability by how much denser medial midsole material there is in the shoe. This is also called posting and most companies add stability in the heel and midfoot as that is the only place they seem to think stability is needed to control pronation. Pronation is generally described as the collapse of the medial longitudinal arch. The problem with that thinking is that the forefoot is an important component of the medial longitudinal arch.